Turn back your mental clock to April of 2012, when Facebook acquired Instagram for the eye-popping price of $1 billion. It was a big story, with headlines all over not just the tech press but mainstream outlets like CNN, Newsweek and the nightly news– who could have imagined a company with barely over a dozen employees commanding a 10-figure valuation?! Like most of you, I watched the story unfold like some kind of tech fairy tale, amazed at what the crew at IG had accomplished so quickly.

But my amazement was tempered with shame and regret, because in a not-so-different world, it would have been my company in the headlines. My phone was blowing up and I did my best to patiently answer the barrage of emails, texts, and calls (Yes, I saw the news about Instagram and yes, I know it could have been us). I laughed it off, but it stung in way that took me a few months to reconcile. It was emotionally draining, because – in large part – my thoughts kept going toward what could have been– and how I let a few simple mistakes throw shade on what proved to be billion-dollar (or maybe even “just” a few-hundred-million-dollar) payday.

I don’t blame you if you’re skeptical, as everyone has heard the story of their friend’s friend – or your eccentric uncle – who insists that he invented cable TV only to have a corporate spy steal the idea from his nightstand sketchpad. Truth is I’m only recounting this now here because I’ve been asked in hundreds of face to face conversations and thousands of inbound social media notes to recount what happened and the reasons why. So here’s my honest take.

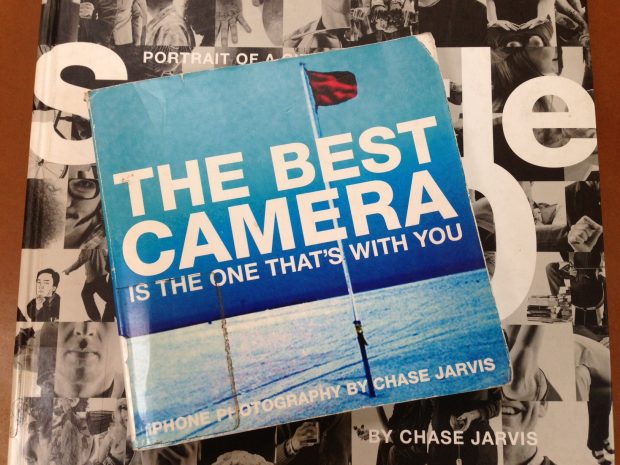

The facts: Back in 2009, as a long time photographer and passionate entrepreneur, I created a photo sharing and filter app which beat Instagram to the market by a year, beat Instagram to 1,000,000 downloads, was featured heavily by Apple across all their marketing channels, was one Apple executive’s favorite apps, selected as one of Wired’s apps of the year, received ongoing coverage in the New York Times and USA Today, was a Macworld’s Best App of 2009, was praised by futurist/technologist Robert Scoble as the “best way to take photos on an iPhone”, and was later described by Gigaom as an app that “redefined the photo app concept in 2009, and still best represents the new photography workflow.; and was credited by the largest english language newspaper in the world as “the app that kicked off the global photo sharing craze.” And yet if I told you its name right now, you probably wouldn’t recognize it.

So WTF happened? (Many of you have asked me over and over) How did I end up on the sidelines, watching as a competitor that we beat to the market by a year sell to Facebook for a billion dollars shortly thereafter?

I’ll tell you in excruciating, painful detail how I let it happen– but first I want to explicitly re-state why I’m sharing this, and why now:

- To share the backstory with those who cared about it way back when. There were so many people (a million) in The Best Camera community 5 years ago. They never got any answers – as in ZERO – as to why we went dark in the wake of so much early success. Y’all deserve to know the story.

- For my own benefit– for catharsis. This has been a weight on my shoulders for the last 6 years, and I’m hoping that sharing it with the world will help me move on and put it in the rearview mirror.

- To pay it forward: I’ve learned countless valuable lessons from the many people before me who were brave and kind enough to share their stories of failure, and hopefully I can help my fellow and future entrepreneurs by sharing my own story.

- As for why now, I was unable to talk about this publicly for legal reasons which you’ll read about later. I get a lot of questions about it, and wanted to answer them now that the legal issues are resolved.

- I want to make extra sure you know what I’ve been working on since this debacle…and more importantly how I used the Best Camera failure to create CreativeLive (a platform that has exponentially more potential and can add more value to YOU than any photo app ever could).

With that said, here’s how my idea went from a rocketship, visionary startup to legal nightmare to dust and then nothing.

The Germ of the Idea

I’ve been a professional photographer for a long time, shooting for brands like Nike, RedBull, and Apple. I’ve also worked with and advised the major photography gear brands like Nikon and Polaroid alongside the likes of Ashton Kutcher and Lady Gaga, and contributed hundreds of videos, thousands of blogs posts on the craft, gear and industries of photography and creativity at large…so clearly the intersection of photography, technology and community has always been core to my life.

But I’ve also been a firm believer that the gear is less important than people think. When you realize what a photograph really is, all the technological stuff starts to fade away. Photographs are not about megapixels or dynamic range, but about stories and moments.

That’s why I was an early champion of camera phones, in a time where pro photographers either dismissed them as crappy toys or bemoaned that they were killing the industry. I think my first cell phone with a camera was a RAZR or a Palm Treo, something like that. It was horrible by current standards– something unimaginable today like 0.2 megapixels– but that didn’t matter. I found joy in just being able to capture all the cool moments I found myself in. Most importantly I found that what was most compelling was that THIS camera, like none other in my life – or in history – was always with me. THAT made it my favorite – i.e. the BEST – camera I had. It wasn’t at all like the pinnacle of the photography industry I was experiencing with shoots all over the world for “Fortune 100” brands, huge crews and bloated budgets. It was the opposite of that. It was quiet. Humble. Certainly low quality and hard to use… but playful and soulful.

Then the first iPhone came out. And another shortly thereafter which took things into 2 or 3 megapixel territory. For the first time, there were several phones on the market that actually became capable of taking tolerable pictures. It was an absolute joy for me, and yet despite my early bliss and optimism, I was still thought (by my industry and most of my friends) to be a little crazy for caring AT ALL about what these cameras enabled in all of us.

As we all now know, this shift in technology became a total game changer, turning hundreds of millions (billions?) of people across the planet into photographers.

Despite the funny looks I got from 99% of my peers, my tech media friends and people on the streets in those early years, and despite the doubters and haters on my blog and other social sites for using my phone when I “was a professional” who had easy access to “a hundred thousand dollars in pro camera gear,” I felt an undercurrent that I could not deny. I was taking some damn good photographs with these junky V1 phone cameras. And more than that, I was having more fun doing it than I was on big time commercial shoots.

But it started to change in 2008. I began to see a lot of traction in my Twitter and Facebook social feeds around many of these photographs – images that most people couldn’t tell were shot with the camera embedded in my phone. And while I loved doing the photography bit, the mechanics of sharing of those images soon became a pain in the ass. After capturing the image on the phone, I was at times using 5 or 6 different apps to add cool effects and then to share them. One for color tweaking, one for cropping, another for sharing to Twitter, yet another for Facebook, etc etc. I had to go into all these separate apps to get the look I wanted and to share each on different social networks. It was workable, yes– but a total kludge.

And then it happened- the “scratch your own itch” moment that’s the start of so many businesses. I had encountered a personal pain-point so great that it drove an epiphany: surely others are having the same problem. Or if they aren’t, they will soon, as the world begins to adopt this technology. What if I can fix this for everyone? Is that a business? Could this be something? I thought so, and — as Apple had just recently allowed software developers to create and submit apps to sell in their “app store” — I decided to make an app that was an integrated, seamless solution for capturing, editing and sharing your photos. I also envisioned an online community focused on sharing these “mobile” photos AND doing the world’s first book featuring only photos taken with my iPhone to show the world what was possible with a camera that my photo peers insisted was a useless toy.

That night I came up with the idea for the app. I had the 3am idea to call it Best Camera, as a reminder to the world of what I had already experienced so profoundly: that the best camera isn’t the one with the best specs, it’s the one you have with you. “In fact,” thought my 3am brain, “maybe that could be the namesake of the entire ecosystem.” The app can be called Best Camera; the book can be The Best Camera Is The One That’s With You, and the online community could live at TheBestCamera.com…or Bestc.am for short since those new domains beyond .com, .net, and .org had just recently been announced 😉

Worth noting is that at this time I looked at this as just a “project”, with the primary goal of simply scratching my own itch, disrupting old-guard beliefs about what was possible with a camera, and helping others experience the joys of modern photography. “Platforms” and “networks” were being built to connect people and apps were selling for $3-5 per download at the time. So I knew that there was real commercial upside, but I wasn’t thinking of this as “a company” per se.

Despite people telling me from every direction I turned that “no one would care about a social network around photography,” I believed it was not only possible, but it was THE WAY I’D WANT TO SEE THE WORLD. The idea of scaling to millions of users was intoxicating, but since my ambition regularly received eyerolls from “people who knew about these things” I felt it was important not to become the “founder” of a “startup”. I wanted to simply remain a photographer who was interested in starting a movement that rallied around my beliefs, my values and an opportunity to help others see the future.

Hammering Out a Deal to Make the App

Although I didn’t know how to make an app, I knew what I wanted to build– not the details but the overall experience. And I knew that Seattle (where I had roots and was living at the time) was a tech-centric city. Surely there were some companies based there who could help me. And so I poked around, asking questions of my friends and making connections within the developer community.

After meeting with a half dozen groups or so, I stumbled into one dev shop that seemed both capable and interested. I won’t reveal the name of the firm– for the purposes of this story I’ll rather just refer to them as The Developers. These guys had done several apps, a few of modest success. They were professional and organized. They were located close to my photo studio. I presented him with my vision of the ideal photo app, of the future of “apps” in general (that they weren’t just a flash in the pan, but that they were the future of a mobile world, that they would become companies and brands in and of themselves). They didn’t see the big vision, but I didn’t need them to see the big vision (or so I thought). They were keen to trade development time for future revenue share– which also worked for me since I didn’t want to come out of pocket for the 6 figures they estimated it would cost to develop the app. And that was enough. Ultimately they were excited by the project and some revenue sharing terms, so we agreed to work together.

Unbeknown to me, the seeds of our eventual failure were sown in the terms of our agreement.

There were two specific deal points that ended up being extremely problematic:

- In order to help The Developers recoup the ~$200k upfront cost of developing the app, we agreed to a deal where revenue from $0-$200k would be split 70/30% in their favor. Then it flipped, so revenue from $200k+ would be split 70/30% in our favor. This meant that their financial incentives were highest during the initial development and earliest updates of product.

- We also needed to map the app development over the next 12 months or so. Knowing that technology could shift, that we’d want to incorporate learnings from launch, etc, so we couldn’t feasibly lay out a specific product roadmap. More precisely, although we both signed off on deploying a long series of high quality product upgrades, we agreed that since both our companies were incented to build an amazing experience the world had never seen, we would be best served by aligning around the exact nature of the product enhancements on roughly a monthly cadence over the coming year or so.

Something seemed a bit off about this approach, but I chalked it up to this being unfamiliar territory for me. If these guys came via recommendations from my community, and they had built some decent apps before, they were solid, right? What did I know about making an app? So I put those fears to the back of my mind and went back to work.

(You might be having one of those moments right now like when you watch someone in a horror movie go into the dark basement alone and you know they’re headed for trouble– “Nooooooo! Chase, don’t sign that contract!”)

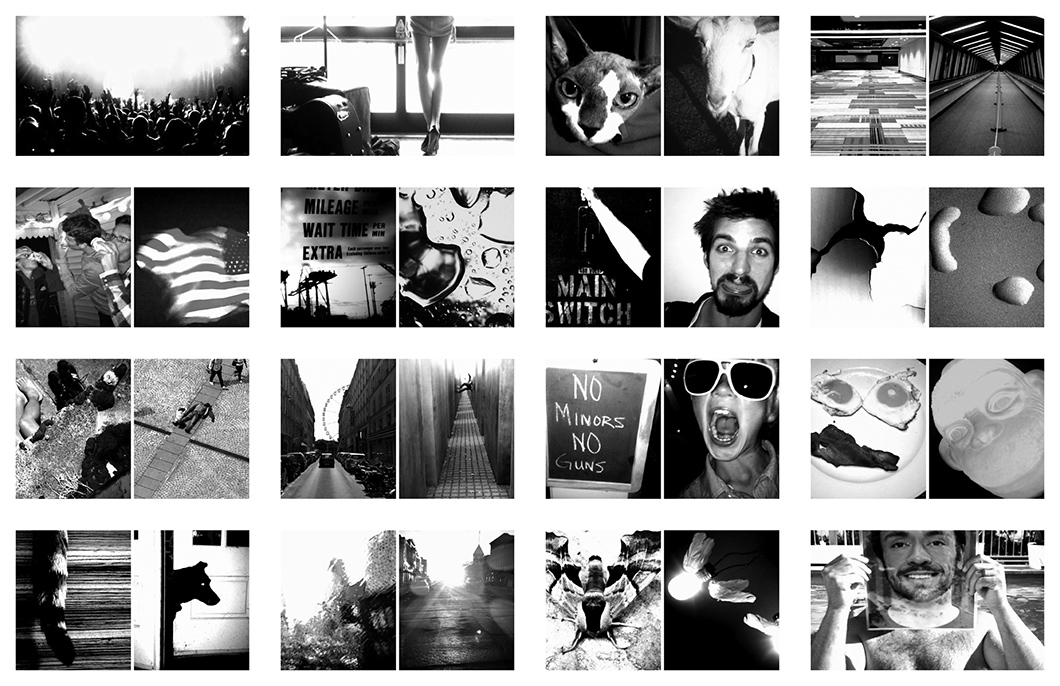

Any of these user experiences/UI/UX or ideas look familiar? The idea of filters and sharing like this seems obvious, but those concepts weren’t around back in mid 2009.

Anyway, after several months of work, we came up with V1 of Best Camera. You could take a picture, add a cool effect and share it with the click one button. It was also the first time you could stack filters. We developed the basic paradigm that’s now commonplace: a handful of one-touch, basic filters/effects and paired those with contrast, fade, etc. The idea of an image “feed” was also completely new. The idea that you could watch a real-time feed of images created by users of the app from all across the world (or some subset of people you “followed”) was was totally new.

Even with all these concepts that were completely new, the initial vision was much grander – like following other photographers you loved, sharing the recipes underpinning each photo’s “look”, etc — but we decided to save the other features for V2 and beyond and go to market with what we had created around taking pictures, adding cool effects, and sharing them to social networks. (I’m guessing this is starting to sound familiar to you)

One of the many other annoying details we needed to figure out was actually getting the thing on the iTunes app store. It can be a bit of a pain to set up an account, so rather than jump through all those hoops (which were much more complicated in 2009 – there was no dashboard, just online applications with fuzzy criteria), we agreed to launch the app using The Developers’ existing account, not our own that we’d have to set up. It wasn’t some major strategic decision, just one of those “wow this is a pain in the ass, let’s just use The Developers’ account and sort out the details later” sort of things.

So we logged into their account, pressed the “go” button and waited to see what would happen… and what happened was way crazier than any of us could have imagined for this little project that started off because I was annoyed by all the steps it took to tweet a good looking photo.

A Surprise Hit

We launched this app in September 2009, along with the book and community website, and were shocked by the immediately – and overwhelmingly amazing response.

We launched this app in September 2009, along with the book and community website, and were shocked by the immediately – and overwhelmingly amazing response.

Over the course of the next 72 hours it went straight to number 1 in the app store. It quickly made its way around the photography community and then the larger tech community and then it got weird. I began getting calls from daytime TV shows and venture capitalists. I was contacted by Apple’s PR department. We were paired with ESPN and Facebook, and within a short window we had 500k users. Oh – and that revenue share? During the drafting of the contract, we had estimated that it would take us 12 months at the 70/30 rev split to pay back The Developers for their time on initial investment. But we were wrong. Way wrong. We had them paid back in 6 days.

I was beyond stoked– everyone at my photo studio, The Developers, my friends close to the project had all poured months of blood, sweat and tears into this thing and it paid off! Everything was going better than we had ever imagined. Or so we thought.

In reality, the problems were brewing beneath the surface, as we soon found out.

Trouble in Paradise

I remember reading a review in CNET at the time that was eerily prescient: “hopefully Jarvis and his software-engineering partners… will continue to evolve the app and not charge extra for updates.”

We allowed ourselves to breathe for a minute (and enjoy a few well-deserved rounds of drinks and high fives), then it was back to work– we wanted to keep the momentum going of our wildly successful launch. And we had a product timeline to keep up with. We’d planned to release monthly updates in order to reach our vision, keep our performance standard high, and exceed the expectations of the community we’d built around our now-award-winning product. The plan was a rapid, iterative development style where we’d do blazing updates to the app for at least a year, going full steam into defining the future of mobile photography.

But as excited and amped as I was to push ahead, The Developers were just as content to sit back and coast. They had earned back more money than their initial outlay to get the app created and the were dragging their feet. I was baffled at first– but then I started to understand how THEY viewed the front-loaded revenue share. They’d already made their initial return, so a similar pace of work for just 30% of the revenue wasn’t that exciting. Especially with all the notoriety they’d received in engineering (the tech behind the app that had everyone talking). There were other, new projects to develop apps for other big companies that captured their gaze… instead of fulfilling their contractual obligation to Best Camera.

I confronted their CEO about the lack of urgency and they downplayed the need to iterate, claiming that all apps were a flash in the pan. They had developed the “lighter” app (digitally analogous to the lighter you’d hold up at a rock concert back in the 90’s) and they’d seen it perform well in the app store only to peter out, so they believed that all apps were destined for the same fate. In their view, it wasn’t about building an app and creating a platform – it was about constantly building new apps so you could earn revenue off the initial sales spike.

Their viewpoint was entirely absurd to me. Where they saw a bunch of short term cash flow projects, I saw a future of mobile-first, billion-dollar companies. The fact that we argued over vision back when signing the contract months prior should have been a huge red flag—but we were too busy, I was too focused on moving forward to believe that I should slow down and align on vision. After all, they were just building what I’d asked — setting up the plumbing– and they didn’t care about photography.

So I did the only thing I knew how to do to help the issue – continue promoting the concept that mobile photography was a huge part of the future of not just the photo industry but of popular culture. I appeared on TV shows all over the world, press of every kind, anything to keep the momentum going to demonstrate that this was a global phenomenon, not just a flash in the pan. And while the crazy growth spike of launch began to scale back from “insane” the app kept selling. I was doing daily interviews. The app was getting featured in all the top media outlets: Wired, New York Times, Macworld, USA Today, etc. Interest in Best Camera continued to grow. Venture capitalists sent me emails saying they’d like to meet for coffee, but I didn’t know enough to care or take the meetings… after all they were “the man”. Publicly traded companies hosted me to meetings with C-level executives and expressed interested in “supporting” our project with whatever we needed…maybe it was capital, or development resources or… maybe even (casually) they could “acquire” the app?

It’s true that I didn’t like the sound of “acquire” – as if it was some toy truck I’d built or a piece of clothing I was wearing that they’d like to own. But even moreso, I knew that we were just getting started if I could get The Developers to see the big picture.

And yet despite being included in stories about app of the year from every major media outlet that published such lists, there was still no forward momentum with The Developers. They were aware of their contractual obligation to develop monthly releases in line with our vision, but they parried off those obligations by obfuscating the contract points as best they could. Instead of building in community features for example, they would translate the app and iTunes description into a foreign language and release a “localized” version in that market. The extent of about 2 hours of work. They intentionally exploited the ambiguity of the contract development roadmap through a lens that meant the least work possible, despite the app continuing to sell and despite the passionate community that was building around us.

The Wheels Begin To Come Off

Little decisions have a way of coming back to bite you.

At this point, I remember I was going to their offices regularly and being made perfectly aware they were not doing shit to help the app and instead were doing the minimum possible to feign real work. I was calling the CEO on it. Heated arguments, voices raised. Dude, what the fuck? There was always an undercurrent ‘photography apps are a flash in the pan.’ It was getting increasingly frustrating for me to maintain buzz and download progress for months, while the app saw no feature additions. To send a signal to the community, I hired another development team, paid them a lot of money, and built out a desktop, web companion experience. Not so much because I believed it in, but because it was all I could do to show “progress” to the community, despite my knowing that the web didn’t really matter – it was all about mobile.

The public feedback on our lack of updates went from a gentle murmur to an angry mob:

A Gigaom roundup concluded that “as a total package, Best Camera remains the best camera app, even if it’s the one that’s also most in need of updating.”

@ChaseJarvis Best Camera app always gets the same updates: bug fixes. Cmon, let’s see something new guys! It’s getting kinda boring.

— Neville Black Photo (@NevilleBlack) February 5, 2011

It went from the occasional tweet or tirade in my social feeds to literally thousands of people begging for an update. But the cold reality was that I couldn’t give it to them. Not just figuratively. I literally had no access to the code. No server access to migrate anything. No access to the app store to see download data, revenue, I couldn’t so much as update the marketing copy. I received irregular financial updates from The Developer (their own reports created downstream from raw data provided by Apple) that when audited always returned errors on their behalf. I was “locked out” in every form of the word. There I was, with the app of the year – a vision for the future of mobile photography, a huge and passionate user base, offers to fund the app – even buy the app for insane amounts of money. But I couldn’t get through to the partners. I was dead in the water.

Having been involved in reasonably public lawsuit with K2 (the sporting goods company) a few years before, I was more than reticent to involve lawyers. The K2 experience had cost me hundreds of thousands of dollars out of pocket in order to protect my copyright under the law.

At this point, I got lawyers involved. The Developers left me no choice. I’ll spare you the details, but suffice to say that the legal battle was very ugly and very lengthy– and while our lawyers were locked in battle, Best Camera was stalled out. My feelings of frustration grew exponentially every day as I watched the world of mobile photography grow and leave us in the dust.

Apple was putting out better and better cameras. There was a guy from Cisco who bought Flipcam for $590 million. I took a meeting with them. I thought it was casual, but looking back now, I understand why they showed up to meet me one day in San Francisco. And there were those other meetings at company X and Y that I took… I think that’s when it hit me for the first time – it was maybe my 4th or 5th meeting – that this little project I had created, was worth $100 million or more. But that never pushed me over the edge, it created more paralysis.

For me that is. Not so much for other people.

Someone Eats Your Lunch

I remember seeing an interview about a startup pivoting and changing name from Bourbn to Instagram. (Instagr.am…funny coincidence on the .am) But if we were in this perceived lean back mode and not releasing any updates, Instagram was doing just the opposite. They were a well funded Silicon Valley startup who was on their second or third pivot and needed to get something to stick. Photos were cool and popular. They had no photo background – just a checkin app with a part of their previous platform dedicated to photos which happened to be more popular than the actual checkin parts. Although they crashed and burned on their launch day (and a few other days after that), they were clearly going after us. And then there were others… Path, Camera+, etc etc, either being developed in parallel or as a direct “remix” now that we had stalled.

But Instagram saw the golden opportunity. They were free. They had decided to focus on photography, and they moved fast. A few months after launch they had over 100k users. A little over a year later, their Series A post-money valuation was $25 million. In another 6 months they would receive another round of $50 million valuing the company at half a billion. Then the billion dollar sale to Facebook, a little less than two years after their launch.

Which brings us back to that day when my phone was ringing off the hook all day and the emotional rollercoaster I was on. The feelings of regret and self-doubt, mixed with vindication– because Instagram’s exit proved that I was right all along about the potential of a photosharing app.

So why has instagram captured the imagination over Best Camera? Cost? Better social? @Scobleizer

— Darren Christie (@whitespider1066) December 7, 2010

That day was validation. At this point I wasn’t really in communication with the CEO of The Developers (it was all lawyers at this point) but I did forward the instagram sale headline to him. The market had validated my original vision and belief in the value of a photo-sharing community to the tune of a billion dollars, and he was forced to see the light.

Despite my frustration that I missed out on what could have been a massive opportunity, I felt strangely calm– almost peaceful. I sat alone in my silent studio, ignored the relentless torrent of notifications on my phone and just sat back, letting it all sink in for a bit. Coming to terms with what was probably my biggest professional failure.

One thing I want to be clear about here: Although I did learn some valuable lessons from this, it was a brutally defeating and ultimately painful experience. I say this because I explicitly want to avoid doing what Brené Brown calls “gold-plating grit”– as she says, “To strip failure of its real emotional consequences is to scrub the concepts of grit and resilience of the very qualities that make them both so important — toughness, doggedness, and perseverance.” In other words, if you don’t let yourself feel the authentic pain of failure, then you’re also holding yourself back from learning.

Winding Down

About 9 months ago we again threw lawyers and dollars at the problem with the simple goal of getting our IP back and cutting all ties with The Developers. And after six MF-ing years, I finally have closure. I have the signed piece of paper, the account in my name, and a check for the royalties that The Developers held for the last 2-3 years. Six years later. Six years of back-and-forth fighting for this thing and we finally got it. A pyrrhic victory for sure, but a victory nonetheless.

And that’s the end of the story from that perspective. That’s the vindication. Gag orders are lifted and I’m finally able to tell this story publicly (trust me, it drove me insane that I couldn’t until now).

When One Door Closes, Another Door – or Maybe a Window Opens

With all the chaos and BS in the rearview mirror I’m finally able to get into a more reflective headspace, and I see things a little differently than I did when the wounds were still fresh. It was certainly a wild and bumpy ride (and one that I’d prefer not to repeat) but if I’m being honest, it taught me so many critical things that I couldn’t have learned any other way– things that were 100% essential to launching and successfully growing my “next thing” — which has exponentially (and I’m using that word precisely here) more opportunity for impact and, ultimately therefore, more value.

I had been kicking around this idea for a new company: an online education platform that was built around the same intersection of technology, creativity and community that drove Best Camera to great heights — similar mission, but way more ambitious in scope. And with Best Camera frozen in legal limbo, I channeled my energy (and frustration) into getting that company off the ground.

That company was (and IS) CreatlveLive.com and today is the largest and best education platform for creatives + entrepreneurs. With more than 10 million students and 2 billion minutes of video consumed on our platform, we feature classes in photography, video, design, music and entrepreneurs. We’ve not “arrived” by any stretch because our goals are 10x where we are today, but we’re off to an amazing start.

How’d this all happen? Of course there’s a million little things that go into making something “successful”, but my personal learnings from Best Camera translated nearly perfectly into the aspects that I’ve contributed to CreativeLive as its co-founder and CEO.

From the failures of Best Camera, a few particulars include us launching back in April 2010 using the playbook honed from launching Best Camera: we built an MVP, made a video, pointed my longtime and loyal community of creatives at our new project, CreativeLive.com and listened to their feedback. We worked tirelessly to improve it based on community wants and needs. Yes, our first class had something like 50,000 people and I knew that (again like Best Camera) we were onto something big. But this time I knew how to ride the wave.

Other supercritical things I learned that were instrumental to building CreativeLive into what it is today? For example, how to talk to VCs and other potential investors. What they look for in an investment opp, how and why some of those things come to be. Remember how I took all those meetings with people who wanted to invest in Best Camera, even though I had little to no intention of taking them up on their offers? Those meetings ended up being the best training I could wish for on how to build investor interest and how to choose great partners with whom to build businesses. I was also keeping a close eye on who Instagram took money from, who they brought on their board, when, etc and was looking at CreativeLive through a similar lens. In short, I was looking for patterns in the dance that is company building. I remember thinking, “All right, I am not gonna fuck around with this one– we’re playing for keeps this time.”

My previous Best Camera mistakes helped me decide why to take our Series A funding from Greylock; why I was open to moving our headquarters to San Francisco (knowing that Kevin Systrom’s relationships with Zuck and everyone else in the Valley were very significant contributors in their success).

The investor side of things is just one of the countless things I learned from Best Camera– there are so many more that I could go on forever. You get the idea.

I’m highly skeptical of the whole “celebrating failure” meme that’s so common in Silicon Valley because I think it’s often used as an excuse or a feel-good platitude, but reality is that failure is an unavoidable part of business. And since we can’t escape it, we have to at least use it as a stepping stone to our next success.

I’ve spent more hours than I care to admit beating myself up about how Best Camera went down, but the honest-to-god truth is that CreativeLive is even more exciting to me. What if the classes we offer to those millions of students have a similar impact — hell, even a hint of that impact — on other creatives and entrepreneurs? What lives will be changed, problems solved, careers and businesses built from that platform? Just like giving someone a fish is less valuable than TEACHING them to fish on their own, we have high hopes for the good that CreativeLive can do in the world. And we wouldn’t have been able to create CL without going through the shit like I did with Best Camera. Not a chance.

What it comes down to is this: The first time you do something, it’s super hard. You’ll probably eff it up. The second or third time, you may be able to get it right on the first try. That’s just reality. It’s practice. Repetition breeds skill. Repetition breeds skill. Repetition breeds skill. So when you do inevitably faceplant, pick yourself up, brush off the dirt, and don’t make the same mistake twice.

One Last Thing

If I get one note per week about Best Camera, I get 50 why I am not on Instagram. The reason this was the case for the last 4 years is simple: the lawyers that were working on the case against The Developers, one of the things they advised me early on was to not use other similar social platforms (if I wanted to sue for damages, being on any other platform where photo sharing was the primary function would potentially devalue that argument). So I reserved my username on Instagram but I to this day have not posted a photo. I have several thousand followers who have expected me to post…and to that squad, I have been disappointing. Until now.

It is abundantly clear who kicked my ass in the photo sharing app game. Instagram is where everyone goes when they want to share their photos with the world. They built an amazing platform – an amazing business – and I’m happy to say that I’m now able to join in the fun.

I’ll be posting my first Instagram photo today. I’m @chasejarvis – hope to see you there.

PS – Have you checked out Affinity Studio, Nano Banana, Midjourney or Meta AI? If not… you probably should!