There are two types of photographers who impress the hell out of me.

There are two types of photographers who impress the hell out of me.

One is the wartime photojournalist, who puts his or her life on line to document real stories and images behind the world’s most dangerous conflicts. [I’ve written about it before — Would You Die for a Photo?]. Without their work, truths get lost, and the stakes are as high as they can get.

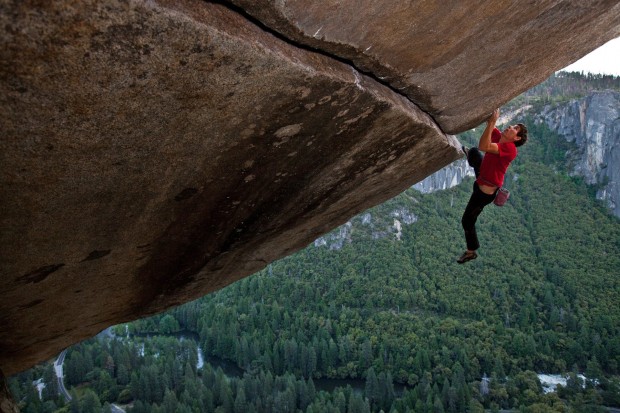

The other is the extreme photographer. I’m not talking about the “adventure photographer” here, the guy who snaps sunset shots of a pride of lions from the safety of his Range Rover. No, I mean the photographer who captures the athletes and adventurers who are pushing the absolute limits of sport in remote and difficult locations. It’s a bit obtusely self reflexive as I often get lumped in with this action sports crew…but there is another level beyond that, I promise. These are the photographers who must both be artists behind the lens and possess the same talents being captured in front of it.

When an alpinist wants to climb the deadliest route in the Himalayas and needs someone to document it, he calls the extreme photographer. When a world class skier tackles an exposed, committed descent in the French Alps, she calls the extreme photographer.

These days, the man who often gets that call is a friend of mine, Jimmy Chin.

If you follow photography, chances are good that you’ve heard of Jimmy Chin. If you’ve ever browsed a National Geographic or Outside magazine, it’s very likely that you’ve come across Jimmy’s work. Jimmy has been featured on numerous magazine covers and been a member of The North Face Athlete Team for almost two decades. He played a key role (both as filmmaker and actor) in Sherpa Cinema’s film “Into the Mind,”, his latest film Meru, and he once survived an avalanche.

I reached out to Jimmy recently asking him to share a little more with us about what makes him tick.

Humble Beginnings

Before he was a photographer, Jimmy was an outdoor adventure junky. He spent a good chunk of his early days living the self-proclaimed “dirtbag” life, living out of his car and bouncing between skiing and climbing.

One day in the Yosemite Valley, an aspiring photographer friend handed Jimmy his camera and showed him how to use it. When the friend went to sell photos from that roll, the company bought only one image, and it happened to be Jimmy’s.

Chase: You’ve come a long way since selling that first image in Yosemite. Tell us about the steps you took from that first paying gig to taking yourself more seriously as a photographer.

Jimmy: In the beginning, it was all about going out with friends and shooting for fun. I just wanted to make great pictures, beautiful pictures. I didn’t think I’d ever make a living as a photographer. It was just something I really fell in love with and did. As I paid more attention to photography, studied photography and photographers and met more photographers, I really began to see the potential of photography as a creative outlet, as a career, as tool to tell stories, as a lifestyle, as another vehicle to see the world.

There were a few turning points for me. Shooting Conrad Anker for The North Face was my first paid gig. That was huge. And the fact that Robert Mackinley, the photo editor [for The North Face] at the time, loved the work and actually published it, was a big boost in my confidence and was also intoxicating. Jane Sievert from Patagonia also started to publish some of my work. I was over the moon that I actually got a picture in the Patagonia catalog. This was essentially the start of my commercial photography career. Rob Haggart, the photo editor from Outside Magazine, also threw me a bone and let me shoot a few things for Outside. He pushed me to look at a lot of photography outside of the adventure and outdoor space. That was a really helpful nudge.

About that time, I also met David Allen Harvey, Jodi Cobb, Bill Allard and a few other Nat Geo photographers at a photo seminar. I got to hang out with David for a few days and he completely opened my eyes to a new way of shooting and new way of thinking about shooting. I remember seeing him shoot for one minute and thinking to myself, “Oh, that’s how you do it.” He smiles, he builds instant rapport, he makes people feel comfortable, and then he dives right in. I’ve tried to embody his approach to editorial photography ever since.

I’ve always been a proponent of “if you’re going to do something, do it right.”

I applied that across all aspects of my shooting — planning, setting up shoots, getting up early, working with athletes and models, working with clients etc. Just being a pro about it.

This shot of Charakusa in Pakastan, taken using his first roll of film in a proper SLR camera, marks the early stages of Chin’s career as a professional photographer. ©Jimmy Chin

Beyond 10,000 Hours

By now we all know the 10,000 hour principle made famous by one Malcolm Gladwell. To become great at something, you have to put in 10,000 hours doing that thing. Practicing. Learning. Taking risks. Making mistakes. When I step back from this whole blog and view it from the stratosphere, sometimes I think it’s all about helping other photographers get to that 10,000 hours. Because it’s that important.

And that’s one of the things that most impresses me about Jimmy. The photography and filmmaking work he consistently produces reflects that of a professional who has achieved a level of mastery. But that’s in addition to his skills as an adventure athlete, which are also world class. I’m talking about a wide range of adventure athleticism — everything from rock climbing and alpinism to skiing and snowboarding. The man is among a very small club of people who have climbed and skied Everest from the summit, and Jimmy did it while taking amazing photos of the journey.

Chase: People want to know how a person can get so good at two things that require a serious investment in time and energy: adventuring (which in your case includes skiing, climbing, mountaineering, etc) and photography (and now filmmaking). How were you able to master the latter without formal education?

Jimmy: I did a lot of reading and research about filmmaking but ultimately it was about going out and doing it. I made a lot of mistakes. In fact, I’d say I learned 9 out of 10 things by making mistakes. I also had some incredible mentors who helped me along the way. I sought them out and created opportunities to work with them in the field. You can learn more in one hour with a good mentor than you can in months of research and/or trial and error. I also don’t think I am a master of anything. I know I will be the eternal student, and that type of attitude helps.

Chase: Tell us briefly about the mentors in your life. How instrumental were they to shaping your path and providing you with education and wisdom?

Jimmy: Many of my biggest life lessons have come from working with or being with incredible mentors. I feel really fortunate that a few amazing people took me under their wings — David Breashears, Rick Ridgeway, Galen Rowell, Conrad Anker, Rob Haggart and countless other people who believed in me. That being said, these opportunities and mentors didn’t just get handed to me or show up out of nowhere. It took a lot of initiative on my own projects and expeditions to create the opportunities. I think people need to see that you have the drive, ambition and potential before they want to invest time in you. I guess I’m now at the age where I am always looking for talented young people to share experiences with. I think it’s kind of a natural progression in life, to be mentored and to mentor others.

I also think it is a two-way street. I get a lot of inspiration and learn a lot from younger generations. I like to think I did the same for some of my mentors. I think that is the beauty of mentorship.

With good mentors, you get to see someone doing something they’ve been honing for 10, 20, 30 years. You get all of their knowledge condensed and shared with you and hopefully, you get to learn from their mistakes and successes. Then you get to add your own perspective or style or ideas to it. It’s incredible.

Death Defier

The extreme side of Jimmy’s profession presents its challenges. To get the shots and capture the story, photographers like Jimmy must push the limits just as far as the athletes they capture. Sometimes those limits push back.

In April 2011, Jimmy was swept up in an avalanche while skiing with a friend in the Grand Tetons. Here’s an excerpt from his journal entry of the event:

[For the full account, go here]“Hope fades and fear rises. It is a dark time. I feel speed, velocity, power, forces unnatural for a body to experience. Then comes the weight. It pushes down. It compresses. It is more and more and more and more… It is unbearable. I hear myself roar from a place I knew a long time ago. It is primal. It comes from my stomach and into my chest. I hold on to my body. Bracing, bracing, tightening for impact. The impact never comes, but the weight gives me no release and I feel my chest compressed and crushed. No chance to breathe. No chance to expand my lungs. It is dark and it is dark.”

Chase: You had a pretty well-known brush with death when you survived an avalanche. How did that experience shape your path?

Jimmy: The avalanche definitely changed my risk calculus. It could be my age and experience too, though. I know I am more conservative now than I was 10 years ago. There is a ton of criteria that I look at when it comes to more dangerous or intense shoots — like who I get to have on my team, how experienced they are, what the risks are, what are the consequences, etc. It needs to feel right, and that often boils down to the people involved in the shoot. For set-up ad campaign shoots, portraits and lifestyle shoots, it’s obviously a lot more casual, but if it’s a heavy shoot and it’s not the right team, yeah, I’ll definitely second guess it.

I’ve definitely taken a few risks to get a shot. I’ve walked both sides of the line, where in some instances I’ve taken a bigger risk than the athlete to get a shot, and others where the athletes are definitely taking a bigger risk. Shooting while skiing on the Lhotse Face of Everest is one of those instances where it felt like I was dealing with a bit more than the skiers. Skiing it was pretty intense to begin with, but stopping and trying to set my edges and balance on an icy, 5000-foot, 50-degree slope at 25,000-feet to pull out my camera to shoot probably added another level of risk than just skiing it. On the other hand, when I’ve shot Alex Honnold free soloing a couple thousand feet off the deck in Yosemite, I’m not exposed to nearly the same level of risk as he is.

Balance and Ambition

These days, Jimmy finds himself in the middle of the biggest adventure of his life: marriage and fatherhood. Even as the demand for his skills are greater than ever, he makes time for his wife, Elizabeth Chai, and his daughter, Marina. He also splits his “down time” between his home in Jackson, Idaho, and an apartment in New York City. Between family and regular assignments, he carves out time to work on a personal project that began back in 2008, after a failed attempt to ascend one of the few remaining unclimbed peaks in the Garhwal Himalayas. Three years later Chin return with fellow mountaineers Conrad Anker and Renan Ozturk and successfully summited Mount Meru, a 20,700-foot vertical wall known as Shark’s Fin. (The feat earned the men the Golden Piton by Climbing Magazine for Best Big Wall Climb of the Year and was voted the #1 ascent of the year by Rock and Ice Magazine).

Chase: Tell us about balancing life and family with work. What does the equation look like these days?

Jimmy: I think experience and time overall has shifted the needle in terms of risk. But, yes, having a family will likely change the level of risk I am willing to accept. I’m not just calculating risk for myself anymore. I will always want to push the edge and step outside my comfort zone, but there are a lot of ways to do that, particularly as a creative. Will there still be cutting edge expeditions in my future? For sure. I’m just going to be a lot more picky about the objectives and who I will go with.

I think you can still push the edge, but focusing on better planning, decision making, choosing expedition partners carefully and keeping it all in perspective — i.e. knowing when to call it — are all part of evolving and refining. At some point, you’re supposed to get smarter and better at how you do things. Hopefully that will be true for me. You also see enough shit go down and eventually you learn when to check the ego at the door. Of course, you can talk about all of this and then there is just plain bad luck sometimes. That’s a tough one. I guess when it’s your time, it’s your time.

Chin is routinely called upon to capture extreme athletes performing in hard-to-shoot venues, like this wing-suit BASE jump from Half Dome in Yosemite. @Jimmy Chin

Chase: What’s next for Jimmy Chin?

Jimmy: I’ve been working on the MERU film for several years between jobs and assignments, so long-form filmmaking is definitely on my mind these days. MERU has been an incredible passion project for me and really opened my eyes to the power of feature-length documentary films. I really dove in deep on MERU over the last 10 months. I’ve been working with my wife Chai on it. She’s an incredible filmmaker and has directed several award-winning documentaries. She won the Tribeca Film Festival Best Documentary when she was 23, and she has been producing and directing films since.

I’ve also had the privilege to work with Bob Eisenhardt, who is a world class editor. I’ve been learning a ton working with both of them. Right now, I’m focused on working with a composer to finish the score, and we’ll be moving in to color and mix shortly. So I guess I would say finishing MERU, and getting it out is what’s on the immediate to do list.

I’ve been working on a couple bigger film projects lately. They are hugely rewarding on one hand, but it’s also really reminded me about the beauty and simplicity of the still image. I will always love photography and will undoubtedly be focused on shooting stills again in the upcoming years. I like the diversity of working in both mediums. Shooting for National Geographic is always an honor and a privilege. They really push you as a photographer. So, I am always looking for projects or assignments to shoot with them.

This shot was taken in 2008 during the failed attempt at the famous Shark’s Fin route on Meru in the Himilayas. Chin would eventually return 3 years later and successfully complete the entire route. @Jimmy Chin

You can follow Jimmy across these channels:

Website

Blog

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Scroll down for more of Jimmy Chin’s work.

Wow amazing, this sport is very challenging and I really like it

Hei, great article, just wanted to say you have a typo. In the section “By know we all know the 10,000 hour principle made famous by one Malcolm Gladwell.” You can delete this reply after, just wanted to let you know.

Also, and I know you see this as me helping you out and not being nit picky, the section in your comments where you leave your name/ address /website could be improved by making the text disappear. Right now I have to delete “Name” before writing my name.

Love your work! cheers

Why is he not on #cjlive as yet? He has such an awesome story to say.

wow! Great work both Jimmy and Chase!