I normally don’t post or link to my mainstream media coverage here on the blog–not necessarily because of the perceived horn tooting, but primarily because a lot of those articles are just sort of vapid, empty whitewashes with little depth and even less bite. That said, I was just featured in the December issue of Juxtapoz Magazine – one of my favorite art & culture mags, one that I actually buy when I see it on the newsstand — AND I can honestly say that this article is different. It’s raw and largely unedited, in a good way. It’s something I’m excited to share. Lindsey Byrnes, the writer, actually knows a lot about visual art and asked some questions that I’ve not been asked before. So hopefully in your eyes there’s something beyond the typical here for your reading pleasure. As always, feel free chuck it to the side OR ask followup questions below. Thanks -cj

I normally don’t post or link to my mainstream media coverage here on the blog–not necessarily because of the perceived horn tooting, but primarily because a lot of those articles are just sort of vapid, empty whitewashes with little depth and even less bite. That said, I was just featured in the December issue of Juxtapoz Magazine – one of my favorite art & culture mags, one that I actually buy when I see it on the newsstand — AND I can honestly say that this article is different. It’s raw and largely unedited, in a good way. It’s something I’m excited to share. Lindsey Byrnes, the writer, actually knows a lot about visual art and asked some questions that I’ve not been asked before. So hopefully in your eyes there’s something beyond the typical here for your reading pleasure. As always, feel free chuck it to the side OR ask followup questions below. Thanks -cj

———

[box type=”note” icon=”none”]

Rather, he’s excited to share his knowledge and pure love of photography with whomever’s interested. He’s an eminent photographer who has achieved great commercial success. He has won awards and is sought after for high profile campaigns. And he’s entered the world of fine art. Attempting to buy freedom is his general philosophy— just about every artist’s dream, is it not? Freedom to create and freely live.[/typography]

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hat struck me most when I caught up with Chase was his explanation that “there are a million paths, let’s judge less the path and judge more the output…” —Lindsey Byrnes

[twocol_one]Lindsey Byrnes: When and how did you develop your interest in photography?

Chase Jarvis: As far back as I can remember, I’ve been a lover of pictures. I had these junky disc and 8mm cine cameras. My interest in all that probably developed from an early realization, a near obsession with the idea that we could capture time, capture stories and moments with tools and a bit of film. While growing up, both my grandfather and father were hobbiest photographers, and they shot a lot of images of me and my friends as young, punk, dirtbag, BMX’er, skater, soccer kids. Strangely, many of my remembrances from that era are memories of the images themselves even more than the memories of those moments. (How very Beaudrillard of me.) That kind of sticking power—that the imprint of a photograph can actually be more powerful than the original memory—made a real impression on me as a young adult. It made me want to pick up a camera and take it more seriously.[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]

How did you go from a soccer scholarship at SDSU to shooting photos for ski and snowboard athletes? What was your first break? How did that even happen?

I grew up immersed in sports and did go to SDSU on a soccer scholarship, but my teens and early 20s were largely a reconciliation of my being a creative, arty kid trapped in a jock’s body. I had the perception that the world was only capable of putting a kid like me in one camp or the other, jock or artist, never both. But it was actually the SoCal skate/surf/punk scenes that helped me realize that it was ok to… ahem… go both ways. So I did. Music, art, culture and sports all jumbled together was my ticket to a bit of clarity. Combine that clarity with the untimely death of my grandfather, who willed me his camera and a bunch of lenses the week of my college graduation. It was a confusing and ironically perfect storm. With new freedom, some self-confidence, some curiosity, and a camera,[/twocol_one_last]

I stretched a little money a long way in Europe, but was soon broke and decided to move to Colorado to co-mingle my love of skiing and snowboarding with my photography. I fell into a crew of talented 20-something snow sport junkies and creatives—many with ambitions to make a life doing what they loved—and although a lot of my photos sucked, I started getting a few good ones. Fast forward twelve months, lots of wasted film and time sunk, and I was licensing images to ski and snowboard companies, shooting every day, and living a goddamn dream.

So, would you say that it all happened pretty quickly?

Considering that for my whole life I’d been told, by no particular person, but sort of ubiquitously by society and social circles, that it was mostly impossible to make a living as an artist, it was interesting how fast it all came together once I actually focused all my energy on making stuff, and sort of declared those intentions the world. So I guess that, ultimately, having the balls to pursue my work with purpose, especially as a career, took years and years. But once I committed, things moved really quickly.[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]

Where many people really struggle with the business aspect, you have been able to parlay your interest in photography into quite a successful commercial career. To what do you attribute that? Was there a lucky break? Why do you think so many other artists have difficulty making that work?

I think it’s more of the ten-year-overnight success syndrome. There hasn’t really been any one break by my counting, just a lot of small successes combined. Two steps forward, one step back—head down to the trenches, make stuff and put it out there in the world to get cheered or jeered. I can’t speak for other artists, but I think the “making it work” part just takes a hell of a lot longer than most people expect or want to give.

What or who inspired you to working commercially rather then focus solely on a fine art career?

Initially, it was purely about being creative. It wasn’t at all about doing commercial work instead of fine art, or before fine art. The pretense around all that was the furthest thing from my mind. It was about getting paid to do what I loved, period. The fact that magazines and companies out there were willing to pay me to travel the world with friends to shoot ski, snowboard, and skate pictures and films made it a no brainer. I felt lucky. Grateful. And for me it beat the hell out of any typically “real” job, or waiting tables or bartending. And it still does.[/twocol_one_last]

Ultimately, art is about making stuff. My time in philosophy at art grad school helped me understand the certain necessities around classifying it, etc. But, at the end of the day, all the artists I know are pretty damn happy just to be making a living by making stuff, regardless of what people call it.

Explain how, at this stage of your career, you see yourself as a photographer. An artistic photographer taking commercial imagery to another level? How would you describe your contributions?

I’m not too concerned with titles or descriptors, so I’ll generally take whatever creative moniker people give[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]me. But I think the most accurate is just “artist”. Not because I’m critical about the term “photographer” or trying to snatch up more creative ground than photographers are typically allowed. But primarily because viewing myself as a photographer, or describing my work to somebody else in that most respectfully simple term, just seems incomplete. I guess I’m sort of a hyphen… Or like one of those German words that is like ten words fused together.

And for what it’s worth, I’ve been told my whole career that being a hyphen, that not having a simple title or a term that describes you or your art is horrible for one’s image, or marketing, or brand, or whatever. Which is total bullshit. I’m doing just fine without a specific label right now. Most people that buy my work or that I work with in a commercial capacity are just fine with not having a buzzword to describe the work. Fitting into a tidy little box isn’t my job— my job is to make stuff and get people to see and think differently.

Let’s talk about the fine art you have been doing and the show that you curated for the Ace Hotel! In blending social media and art, can you explain this inspiration and how it is going? Do you feel this is an actual step towards that segment of the art world that people need to classify as “fine art?”

Let’s face it: we have hit a critical mass of cameras in our culture. They are nearly ubiquitous. Point and shoot cameras, Polaroids, web cameras, surveillance cameras, DSLR cameras, and particularly mobile phones. An earlier body of my[/twocol_one_last] [hr] [hr] [hr] [twocol_one][box type=”alert” icon=”none”]HAVING THE BALLS TO PERSUE MY WORK WITH PURPOSE, ESPECIALLY AS A CAREER, TOOK YEARS AND YEARS.[/box] work called The Best Camera is The One That’s With You focused on mobile phone photography and yielded the first photo book on the subject, and the first live, unedited feed of mobile images from around the world. Celebrating that we can now be whimsically, instantly, in-the-moment free to be more creative than ever before, my current work has come to rest not in the artistic exploration of what creativity these devices afford, but specifically the content of the snapshot images that spring from them.

Like it or not, the snapshot has become the most meaningful visual storyboard we have of our ‘being’ in the world because it is pure, direct, unmediated visual expression. It refreshingly lacks academic influence or vogue and invites accessibility and participation. The intention to capture a moment is fundamentally present but not over thought. There is a raw, metaphysical power present in snapshots—especially some aggregate of them—that cannot be denied.

My recent installation at Ace Hotel NYC called Dasein: An Invitation to Hang was a deeper exploration of this concept, a celebration of the snapshot. It involved hanging thousands of printed snapshot photographs, my photos, the photos of some of the most well-known photographers and celebrities of our time, and images from photographers all over the world, all curated and displayed anonymously together throughout the course of a month. Hundreds of new images were curated from digital submissions to InvitationToHang.com, printed and hung in the physical gallery space every day for 30 days, to create a living, breathing, piece of artwork that was as dynamic and fleeting as the images from which it emanated.

How’s it going?

The installation at the Ace just wrapped up, but I can say pretty definitively that it blew all of my expectations out of the water. All told, more than 15,000 images were a part of the project, from thousands of artists and something like 150 countries. The Ace extended the show three times. I was humbled and, quite frankly, blown away to be visited at the Ace by curators from most of the major NYC museums, including The Met, and MOMA. Given some of those meetings, I’ll go out on a limb and say that the concept is really just beginning. I have high hopes that it can grow, evolve, and continue in one of those major venues. My inspiration for creating work like this lies in an attempt to get us to rethink and re-contextualize modern photography, and the culture of making and sharing art. Anything that attempts to do this without tapping into social media would be remiss, right? So that’s where the social media stuff comes into some of work.[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]It has enabled a new kind of art that is widely interdisciplinary, interactive, and symbiotic, and most importantly, it requires the participation of others. Such a transformative art has only become possible in the last ten years, which for lack of a better term, I call social art. Not unlike street art and graffiti, the spirit embodied is one of immediacy and accessibility, of creative empowerment and self-expression.

While it’s my name that is screened onto the wall at the Ace installation, it’s more complex than that. The structure of this installation alone is an open challenge to the status quo. Not only did well-known artists hang next to unknown artists, but everyone owned it and no one owned it. Stuff like this is may be difficult or impossible to categorize, but that’s part of what is exciting. Not only does it celebrate new notions of openness, accessibility, distribution, and the democratization of creativity, but also these themes are appropriated by the work and become meta-narratives beyond the underlying subject matter.

You are completely plugged in to the newest ways to promote your work including CHASEJARVISLIVE, which live streams your photo shoots. How do you come up with these ideas, and what is the advantage of a live stream like that?

That’s a fun side project. The back-story is that I started messing around with live Internet video broadcasts a couple years ago and it became pretty interesting to me. We streamed a couple live photoshoots and a lot of people started watching, like twenty or thirty thousand, and sort of figured we were on to something. It’s not network numbers, but I didn’t give a shit. It’s unique to broadcast TV in that it’s interactive, so people in Malaysia and Russia and New York and South Africa can ask the guests questions via Twitter, for example, and they get answers on the show in real time. It is a great way to bring creative, culturally curious people from all over the world together. Since 100% is under my control, it gets to be uncompromising and laid back and whatever format we want. And it’s okay to swear and drink beer and stuff like that.

Over the past year we’ve become more organized, made more of an actual show, and called it Chase Jarvis Live (Chasejarvis.com/live). But it ultimately isn’t about my work at all. I’ve tailored the show toward sharing with the world some of my insanely talented friends who range from Pulitzer Prize winning photographers, Grammy award winning musicians, New York Times best selling authors, and also some of my homies who maybe haven’t got a ton of traditional recognition, but deserve it or will get it soon. It is a bit selfish, I suppose, because I love spending time with these great people and they inspire me personally. But, fundamentally, my hope is to connect my audience with these guests and vice versa so that everybody wins. The show keeps growing, so I think it’s working.[/twocol_one_last]

I became familiar and a fan of your work after a friend showed me the video you made for Nikon showcasing the D7000; how did you begin working with Nikon, and what is the scope of your relationship?

I don’t recall when Nikon first reached out, but my earliest memory recalls when I was commissioned by them to create the campaign around the world’s first HDSLR— the D90. It was the first camera enabled with the technology to produce not just stills, but also video with that shallow depth-of-field, cinematic look of a camera that, before the D90’s time, cost $100,000 or more. It’s hard to visualize in these terms now, but that shit was revolutionary just a few years ago. I shot the still and video campaigns for the launch of the camera and made a behind-the-scenes video, which became the first viral video of its kind, clocking millions of eyeballs. Like all things, a little talent with a lot of luck converged at the right place, right time. It was a big honor getting to throw the first stone into the pond. And since then, it’s been so amazing to see what this technology has enabled, completely juicing the indie digital filmmaking revolution.

The above D90 gig went so well that I got invited back the following year to shoot another campaign, this time for Nikon’s newest HDSLR camera, the D7000. That work is the film your friend showed you, and it was even more fun in that I got to actually make a short concept film that had been brewing in my head for a while. Called Benevolent Mischief, it melded street art and graffiti with originally scored classical music. Then I immediately released a remixed version of that film in music video format with rapper Victor Shade. Those shorts, plus a ‘making of’ video, had an even greater reach than the D90 stuff, so everyone had a good bit of fun and came out smelling like roses.

What inspires you right now?

Right now most of my inspiration is couched in a few camps. One is straight up snapshot photographs, real un-moments seemingly unremarkable until you look more closely. Ari Marcopoulos has a great saying about shooting the everyday stuff; he calls it shooting things that are “at arm’s length.”

That’s interesting—it’s close to me, both physically and emotionally. Perhaps I find these images most interesting because they comes from a definitive point of view— one that only I could have, a photo that only I could take.

[box type=”alert” icon=”none”]I GUESS I’M SORT OF A HYPHEN … OR LIKE ONE OF THOSE GERMAN WORDS THAT IS LIKE TEN WORDS FUSED TOGETHER.[/box]Another inspiration, a constant, is people, not famous people, but the almost famous. Because[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]fame is weirder, wider, and more abstract, intangible, and complex now more than ever before.

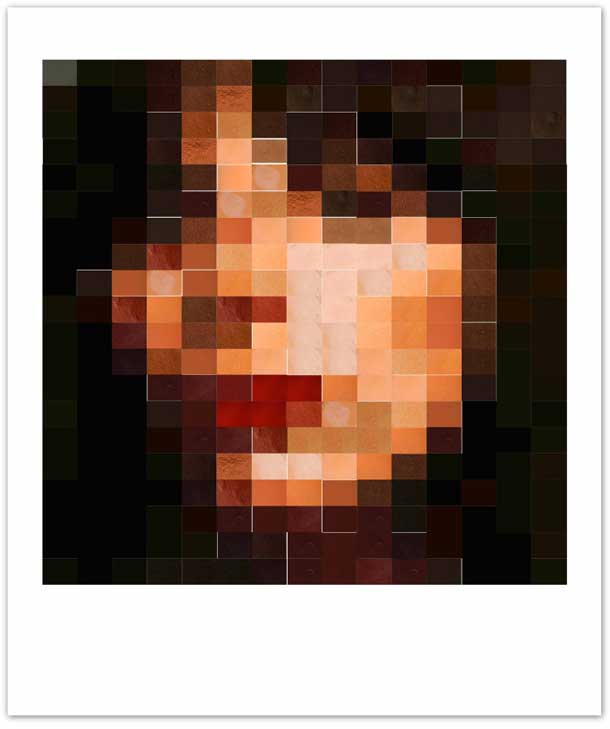

The third camp involves mosaics of images, patterns, or aggregates of images that come together to say, do, or make something larger than an individual photograph, usually of people from the above genre.

The Dasein project is indicative of all three camps. The latest thing I’m wrapping up right now for the Polaroid 50/50/50 show at Phillips de Pury next month is also in this lineage, large mosaics where hundreds of individual images become pixels in a larger image. I think of them as little cultures or societies— each photo needing the photos next to them to stand up. A lot of meaning resides in the one image, one person, one photo, one expression, but a much larger meaning emerges when aggregated with the other, larger cast of characters.

When commercial companies seek you out to create original, jaw-dropping campaigns, how are you inspired for each project? What contributes to the actual execution? Do you work with a big production crew or a small team? Do many first ideas get rejected, and if so, does that impact your personal project ideas?

It’s much more collaborative than it used to be. I’m brought in a lot earlier in the conception phase now, and am actually inspired by many of the parameters, which can really spur creativity. In some ways, I think there are constraints placed on artists when doing commercial work of a certain size. Although there is a common belief in the art world that creative constraints are bad, I don’t see it that way. I think that interesting visions can be inspired through boundaries. Limitations seem to drive my creativity, forcing me to think on command, which I think that is a great challenge for any artist.

The crews I work with range from just me to fifty or more people on a commercial set.

Few of my first ideas get rejected, but almost none of the final products look like what they start out looking like. It’s almost always a collaborative, evolutionary process.

And when you can’t find inspiration?

The best thing for me to do is forget about my need for inspiration and go out and live a little more. Get uncomfortable. Live some other art. Travel. Walk the earth and get into adventures. I believe pretty strongly that this sort of thing comes from deep inside. So it requires some shake-up. Ironically, for me, getting inspired is ultimately about forgetting about looking for inspiration, because in that mode, you’re always judging. And when you’re judging, you’re not nearly as open to some inspiration that might crack you upside the head. Escape and engage.[/twocol_one_last]

I’ve been a Juxtapoz reader for awhile now – heck of a magazine for inspiration.

Totally surprised, in a good way, to see your interview when I turned the page.

Congrats.

Alex

“The best thing for me to do is forget about my need for inspiration and go out and live a little more. Get uncomfortable. Live some other art. Travel. Walk the earth and get into adventures”

This is where I am at right now. There is a need to stop trying to force the inspirationa and let life bring it to you.

Cheers, A great read, and an even better find with Juxtapoz now being on my ipad.

juxtapoz on ipad is a treat.

glad you like the incidental quote 😉 I believe it with all my heart.

Escape and engage. Roger that! Thankyou so much for sharing this awesome piece of your side. I always look for stuff online to get to know more about you, read your mind and your thought process and so forth. You are one who have helped me develop a creative vision, so the fodder always falls short soon 🙂 Please keep sharing.

Thank you. Lots of love and respect!

Loved the interview, love Chase as a promoter of populist access to art, creativity, and free expression through photography. Thanks for posting this here.

Just an irrelevant side note: maybe *I* am a snob, but it does cheese me off when I read journos who misspell simple words like “hobbyist” and “pursue.” *gnashes teeth and slinks away*