Geek alert. Although the mentality stems from the last century, the megapixel wars are not over. It is, however, safe to say that those of us familiar with our cameras have started to realize that they are much more than megapixels + dynamic range. There are other factors that we have come to admit are important to consider – case in point, the sensor. Some are noisy, some are big, some are juicy, others are…well… you get my point. These apparent truths prompted a conversation with my friend Sohail and led him to this in-depth post about the comparison of digital sensors and processing systems that go into today’s cameras — all with the emulsion (the photo sensitive side of film) discussion that used to kick around in the era of film. It’s all coming full circle now… Take it away Sohail. -Chase

A few months ago, I made a switch in camera platforms. Comparing images taken with a 5D Mark III and a Nikon D800, I found that there was something about the Nikon image that I really liked, something that went beyond the standard things that can be quantified, like its 36MP resolution, or its 12 stops of dynamic range.

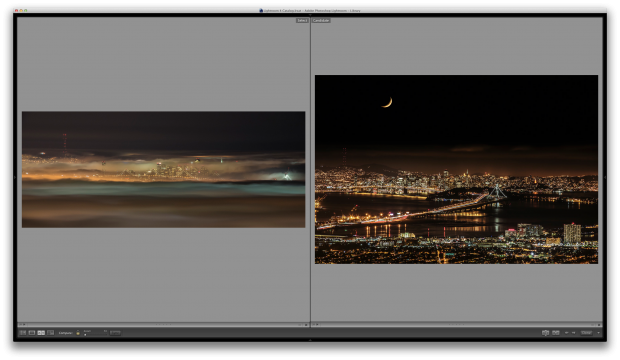

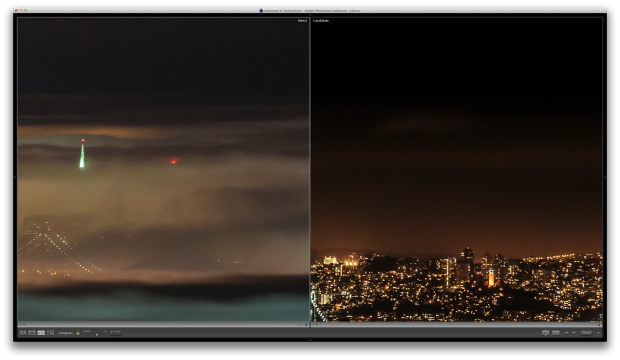

D800 shot on the left, 5D Mark III on the right. Fog-shrouded Bay Area, treated in Color Efex Pro 4. © Sohail Mamdani

The atmospheric conditions for the two shots were different, but even accounting for that, the 5D Mark III image was uncomfortably crunchy, with some pretty serious color noise and banding in the shadows. The D800 shot, on the other hand, had amazing tonality, and the noise was mostly luminance noise, smoothly rendered, almost organic, like film grain.

I’d love to tell you that this was a moment of epiphany. It would be great if I could say something like, “And at that moment, it was as though the heavens themselves had opened up and poured the sweet song of angels down upon my ears and I realized I had found the camera I’d been waiting for all my life.”

Yeah, that didn’t happen. Though I did end up switching to Nikon, for a number of reasons. (Let no debate rage at this point…please).

An idea is born

Comparing the two images — especially the comparison of the Nikon’s luminance noise to film grain — did serve to make me aware of something that I think has been happening for some time now. Though the megapixel wars aren’t over by any means, we have started to look at our DSLRs as more than the sum of their megapixels.

I’m old enough to remember the halcyon days of film. Back then, we had vigorous discussions about tabular versus classic grain, T-Max vs Tri-X, why no one should shoot caucasian skin with Ektar 100 and why only masochists shot with color slide film (Chase tells me this was his primary mode). The old darkroom hands swapped developer recipes back and forth, or kept them close to the vest, like preciously guarded state secrets, while the young hands spent hours in the darkroom with pieces of cardboard punched with holes for dodging and burning under the enlarger.

It was with much amusement that I realized the parallels in our comparison of digital sensors and processing systems that go into cameras with the old film hands’ discussions about various emulsions.

Really? What parallels?

Let me break it down for you.

In the old days, every film could be said to have a purpose. Fuji Velvia was the landscape film, with awesome, popping greens. Kodak Tri-X was the photojournalist’s film, a 400 ASA film that you could push to three stops and shoot at ISO 3200. Kodak Portra was, as the name suggests, for portrait films.

We left a lot of that specialization behind when we went to digital – and thank goodness for it. Unlike real emulsions, however, digital emulsions can’t be switched out — unless you’re shooting medium-format or with a Ricoh GXR system — so it made sense to have a more “generalist” chip doing the job. Instead, we resorted to post-processing to recreate the look and feel we wanted, and this is an approach that still yeilds dividends today. The cityscape above was finished in Nik Color Efex Pro 4, for example, and I applied the Kodak Portra 160 effect to it to make it look the way I wanted.

But look around you. In the last couple of years, specialty sensors are, in fact, making an appearance. The Sigma SD–1, with its Foveon sensor, which purports to deliver a file that claims to rival medium-format images, for example. Or the proprietary X-Trans sensor in Fuji’s X-Pro1, with its EXR processor and built-in film effects, which does away with the standard optical low-pass filter and the traditional Bayer array of pixels, with fantastic results. Or the aforementioned D800E, with its ridiculous resolution and dynamic range. Or the most blatant of all specialty sensors – the Leica Monochrom-M with its black-and-white-only sensor.

That piece of silicon in your computer that sits on the film plane is starting to look a lot more like film, isn’t it?

Okay. But why does any of this matter?

Simple. It matters because when you reach for your wallet to buy or rent your next camera, accepting that there are differences in sensors beyond megapixels is going to go at least some way towards helping you pick your next camera.

Let me give you an example. If you’re the kind of shooter who likes HDR photography, then knowing that the D800E has incredibly dynamic range might help you chose that over, say, a Canon 5D Mark III. Or, if you’re nuts about great, popping, luscious colors, you might chose an X-Pro1. Black-and-white enthusiast? That Leica Monochrom might have your name on it.

The realization that the sensors going into digital cameras have their own unique characteristcs, just like the film emulsions of yesteryear, can actually direct your choice of cameras. I’ll happily put up with the X-Pro1’s foibles, for example, to get that awesomely luscious color out of it.

Wait a second. I can do that Velvia film look and get those colors in post, can’t I?

In many cases, sure. There are some great programs out there now that can help pull color out of RAW images like never before. And if you have the time, energy, and funds, you should invest in them.

You are, however, going to have a much better starting point if the sensor in your camera gets you that much closer to the look you want to begin with. To go back to images at the beginning of this article, I’m sure that with enough massaging, I could work that color noise out of the Canon image, deal with the banding to a large extent, then apply the film grain of my choice. I tried that, in fact, and like my experience, your results may not meet your expectations. After an hour of work on it, the image from the 5D was still murky in the shadows, and didn’t have the look I wanted.

The Nikon image, on the other hand, took less than ten minutes to get it to where I wanted it.

Conclusion

Unlike the days of film, you don’t need to delve into the minutae of the differences between film grains, the response curve of Portra 160 vs 400, or the tonality of Neopan Acros 100. But if you understand that — and accept — that modern sensors do, like their film analogues, have quirks and capabilities beyond those listed on the camera’s spec sheet, then you’ll be able to make a more informed decision about where you spend your money.

In the end, you’re going to make the image, not your camera. But it helps to have a great starting point.

—

Gear provided by BorrowLenses.com – where still photographers and videographers can rent virtually everything.

It looks like the many concepts you might have offered on your publish. These are really genuine and can certainly perform. Nevertheless, the discussions are extremely limited first of all. Could you please stretch these people a little bit out of next occasion? Appreciate a post.

Great article and stunning pictures. Sad, but I think SLR will disapear soon, It is good idea to invest in film strips, after few years it is gona just dissapear…

You have to push the Canons a little to right to get rid of the banding. You probably should have done a little research on why the banding was happening..

WOW — lighten up people!!! The author did a great job analyzing a certain quality and feel of digital sensors — that was the whole point of the article and he conveyed it perfectly!

those 2 pics you compared between nikon and canon could not have been a worse choice for comparison !!! dude – you have zero midtones (or anything close) in the nikon shot and the canon has 80 whispy midtones – NO WONDER there is slight grain and banding at low light like that !! If it was reversed I’m sure the nikon would have been worse !!

You’re weird to call yourself a pro anything with basic mistakes like that

peace