Thanks, Chase. One month into my tenure as executive director at Photo Center NW, I’ve been contemplating photography and its history here. A college professor once told me that history was the freest of all liberal arts, because “it asks only that you take it for itself.” That sounds so easy! But history, like photography, has many layers and viewpoints. Each time you examine it you may discover something different; and how you perceive it tomorrow can shift depending on time, and the weather, among other cosmic factors.

So. Photography. Northwest. Growing up in Puyallup, my experience of photography started with family albums, progressed to working on the junior high school yearbook where I first entered a darkroom, and culminated with work trade for a portrait photographer in order to share precious “senior pictures” with my friends. My experience of place was slightly more colorful—the Puyallup Valley was at that point still predominantly agricultural, and I hated both the raspberries and the daffodils that were perennial signs of spring, because they meant….a lot of weeding. A lot of work. Now I sometimes immerse my hands in the soil just to remember that. I have few photographs from those years to stimulate my recollections, but recently discovering an Asahel Curtis image from 1935, of a young woman picking berries, was, perhaps, better than a snapshot of my own. She looks elegant. But I know she is also tired. She looks happy (from the berries one consumes throughout the day, I like to imagine). But she was probably also pleased for the small income she derived from this delicate task in the years of the Depression. The facts of this photograph are limited—there is a woman, in a berry field, in Puyallup. The stories I can tell myself and you from those three simple facts could go on for hours. That is the subjective, enthralling power of photography. And the challenge with any single approach to history.

When your days begin in the shadow of Mount Rainier, you all too quickly settle into the ultimate, succinct phrase to describe Northwest perfection: “the mountain is out.” My challenge in appreciating landscape photography stems from my eager exposure to the occasional view of that peak. I have seen many photographs of Mount Rainier. I know without a doubt that the person making the photograph felt the gut-wrenching beauty and mystery of a momentary encounter in nature, but rarely does the photograph take me to the dizzy heights I feel seeing the mountain myself. Perhaps I place too much expectation on the photograph? But many other subjects, photographed, resonate with me for years, often moreso than the lived moment documented. Landscape as a genre is, for me, harder. And yet once in a while an image will come along (Mary Randlett’s Island Wave is one such photograph) that is undoubtedly a landscape view, and yet achieves in the print the transcendence I find in experiencing nature here firsthand. I was more familiar with Randlett’s portraits, so was truly delighted to absorb her simple, graphic approach to treelines, shadows, and water—essential components of this place.My education in photography increased exponentially in my years at Bard College, and after, and through that exposure from across the country I continued to learn volumes about the histories and future of this region. Book projects have introduced me to Merce Cunningham, who came from Centralia, WA to Cornish College of the Arts and went on to transform modern dance; to members of the Black Panther Party, whose second chapter was in Seattle, and who left a legacy of free breakfasts and lunches for children, community food banks and health care clinics that still function on Capitol Hill today. A portrait of Morris Graves by Imogen Cunningham took me to the Northwest School of painting, and then to Cunningham herself, who I had only associated with the Bay area zeitgeist of twentieth-century photography. But no, her life and work began here—she picked up her first 4×5 at the University of Washington, and she always found a way to make significant work, regardless of the simultaneous demands of being a wife, a mother, a daughter, an assistant, a friend. Decades later I still struggle with finding time, as she did. And yet I am still compelled by the creative process to keep producing (books of photographs—I leave the hard work of the photographs themselves to others).

Like Cunningham, Minor White also found his way from the Northwest to the Bay. He originally left Minnesota to head to Seattle, but ran out of money in Portland, discovered the camera club there, and stayed until his service in WWII. His affection for the region brought him back to workshops in Oregon until the last years of his life. From White’s history in Oregon I stumbled into the present, toward Carrie Mae Weems, who I worked with in New York but who grew up in Portland; Chris Rauschenberg, a pillar of the contemporary Portland scene, and Robert Adams, a sage of my photographic journey, who inspires me to do more for humanity, for the earth, and for photography simply through the quiet determination with which he lives his life. A shared affection for Adams and his work was obvious when I met Eirik Johnson (who, though from Seattle, also logged time in San Francisco—noting a pattern here?). After years away he and his family have returned to the Puget Sound. His Sawdust Mountain project is an authentic exploration of the complexity and beauty of this place. Eirik graduated from University of Washington, also the alma mater of my friend and colleague Isaac Layman. Both were taught by Paul Berger, who in his own studies was inspired by his one-time interaction with Minor White at a lecture in Rochester, NY. We often think of history as the past, but these intersections make it ever-present for me.

Legendary Bay-area music photographer Jim Marshall came to Seattle in 2010 for an exhibition at EMP that included his photographs of Bob Dylan, the Beatles, Janis Joplin, and yes—our very own Jimi Hendrix. Though I knew some of the local legends featured in the exhibit including Alice Wheeler and Charles Peterson, I met Jini Dellacio through that exhibit, and more recently made the acquaintance of Lance Mercer and Dave Belisle, who have had longstanding relationships to Photo Center NW.

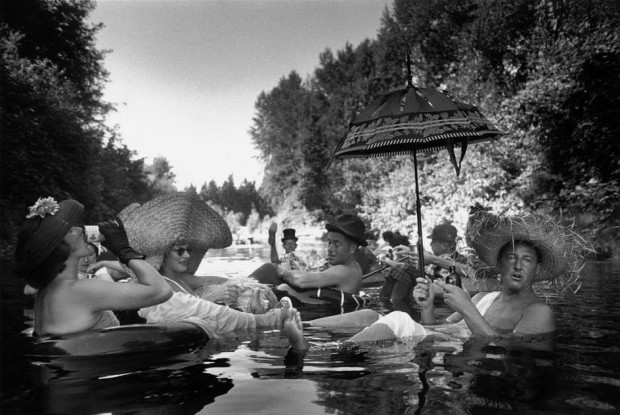

There is more. Photography and glass. Photography and industry. Photography because it is a modern medium, the language by which we speak today. Always more. But a photograph I will hold in my mind’s eye in the busy days and weeks ahead is Burt Glinn’s Seattle Tubing Society, 1953. We as viewers can sometimes immerse ourselves so completely in a frame that we cease to consider the photographer. I looked at this image many times, taking in the joy, the community, the experience of sun and trees and water (yes, I read those as sun hats, because they would be highly ineffective in the rain. Interpretation again). I laugh when I see this photograph, and laugh again realizing that the photographer must also have been in an inner tube, on the water, to achieve that particular angle. If that image reflects the spirit of the Northwest, then count me in. It’s good to be home.

Many thanks to the one and only Chase Jarvis for offering us an opportunity to share with you some of the photographs on our minds these days at Photo Center NW; most of the images referenced will be on view in our gallery beginning today, September 20, and up for auction at our annual fundraiser October 18. Learn more here.

—Michelle Dunn Marsh

Burt Glinn, Members of the Seattle Tubing Society, Seattle, WA, 1953. Courtesy the estate of Burt Glinn and Magnum Photos

I am genuinely glad to glance at this webpage posts which carries tons of

valuable information, thanks for providing these kinds of information.

Dear Michelle and Chase,

This is an absolutely beautiful article and show on the importance of blooming where we’re planted. The images and the history you recount are rich and compelling. These photographs and artists tell fascinating stories about moments in time as they reveal the depth and wonder in our everyday lives, And yet our connection together, in and through photography, and throughout our lives (and yes through the internet) is undeniably global, unified through the vision of one sun reflected in silver on paper, electrified through lights on film, or pixels illuminated in binary code. Thanks for sharing these images, their history, and your time to find this thread of unity, a local beauty communicated throughout the ages by so many different artists finding time to refine and write with light “A Legacy of Great Local Photography” currently exhibited at Seattle’s Photo Center Northwest.

It’s amazing to see such a long history of varying photographic material in a local institution.

MOre than the pics, its the vision of the photographer.