—

Since each of my staff are experts in their own right, fielding a growing amount of questions from you fine folks–and it’s nice to get a change in perspective–you’ll be seeing more and more posts from these talented people in weeks and months to come. Today, Scott takes the reins and answers a popular question about making great black & white images, with a case study to show you how. Take it away Scotty…

—

The world is not black and white…but the Seattle 100 post production is.

Following up on the popular guest blog post I penned about the sand jumper image, I thought I’d use this platform to respond to the string of questions I’ve been getting about how we got the striking high contrast black and white aesthetic in the Seattle 100 project.

In the tradition of this blog, this is not going to be a tutorial, rather a theoretical discussion with some visual aids to help illustrate. Post production, like photography is a vast set of tools which give an artist infinite ways to arrive at a finished product. Do not get caught up in the tools, they’re just tools.

Glad that’s out of the way. Now, here’s the theory of the Seattle 100 post production…

- Make the whites white and the blacks black.

- Emphasize interesting textures and features.

- De-emphasize distracting textures or features (see #1).

- Build contrast by adding layers (this can be very incremental).

- Black and white is a friendly medium, don’t be afraid.

- ‘Because it looks cool’ is a perfectly acceptable reason to do something.

Now a bit of the nitty gritty. I’ll dissect the layers briefly in order to illustrate the concept of creating real blacks and whites, and building contrast with layering. Before any of that is done there is a quick retouch process to remove surface blemishes. Since these are portraits and not glamour shots, the point of the retouching is just to be friendly with little bumps and blemishes, not to change the character or structure of the person in the image.

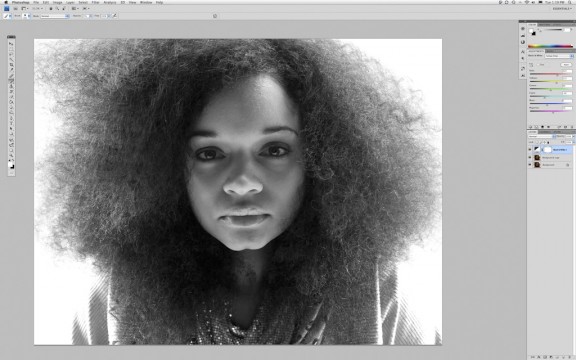

Next comes the conversion from color to black and white. I used a black and white adjustment layer set to yellow filter. The yellow and red filters tend to be very kind to skin, and generate strong contrast, a good initial starting point.

Converted to monochrome with black & white adjustment layer set to yellow filter. Yellow filter helps to make smooth skin.

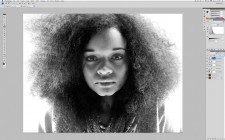

The rest of the final look is developed using only a series of levels and curves layers with some strategic use of masking in order to emphasize the good and hide the bad.

Take a look at the series of images. On one hand, there is a drastic difference in terms of the impact of the image. On the other hand, all of the elements were there in the original. The direct striking gaze, the smooth dark skin framed in darkness, the exquisite wild hair. All of the post production efforts were aimed at enhancing the image by drawing the eye to the most compelling parts of the portrait.

If you were to pick this image apart you’d find that the blacks are very much black, there’s no data in the areas that appear black. The same goes for the white. Those tones serve as the absence of detail so that your attention is drawn to the person in the frame. Conversely, you’ll also find that there is detail in every single pixel of her skin, eyes, nose, and lips. These are the areas that Chase was working hard to capture in the image, and those are the areas that are highlighted in the post production.

Each final image in the book was given it’s own custom retouching, and the techniques varied quite a bit depending on the person and circumstances. What did not vary was the aesthetic concept, which served as a constant guide in both the photographic and post production processes. The real trick is not to figure out the how, there are always a thousand ways from A to B. I could have substituted channel mixer layers, dodging and burning, retouch brushes in Aperture, etc. for the curves and levels techniques I used. The real key is to develop a vision, and then do whatever works for you in order to execute. To check out the rest of the Seattle 100 images visit www.chasejarvis.com/seattle100.

Scott Rinckenberger

Great stuff man. Thanks for the tutorial!!!

Hi Scott

Well done!

One question:

I’m curious why you use curves for shadows and levels for highlights predominately?

Thanks

George,

Great question. I generally use Curves when I want to influence both the midtones and the darks (or lights). I use levels when I want a more isolated tweak to just the highs or lows. In the case of this image, I had to be a little more gentle with the darks because it was easy to loose detail in her face and hair in the shadow areas, hence the curves. It should be said that either Curves or Layers can be used almost to the exact same result, I just segment their use in my head.

Thanks for clarifying this, I had the same question. Typically, I find myself working only in curves, since it makes me feel far more advanced that I really am. I’m picking up what you’re putting down however, and like how the visual difference makes the doc more easy to navigate when you want to tweak your adjustments. Thanks Scott. Keep ’em coming.

Thank you so much Scott, I am so thrilled to see your guest blog. I look forward to more of your guest blogs. At the moment I don’t actually have Photoshop, and do all of my adjustments in Aperture 3, so I don’t quite understand the different layers you talked about, but I still enjoyed reading it.

Scott, wonderful post. I have been doing quite a bit of black and white editing and have taken as my benchmark Avedon’s work in the American west. I was surprised when I realized that some peculiar aspects of the photos were a result of the photo editing. The photo of Billy Mudd, looks almost as if he were wearing a mask, but it is a result of dodging on the face. The dodge/burn notes for Lyal Burr (which show up in Chase’s “purists beware” post) enable one to appreciate the changes in the final photo. Interestingly the doge/burn notes are not Avedon’s. According to Laura Wilson, Avedon was quite vague in his requests, trying to heighten the emotional impact of the photo – the detailed instructions belong to Ruedi Hofmann. Steve McCurry has also claimed that he hands the editing to an assistant. So, after that long preamble, my question is, how collaborative is the editing over at your studio? Do you try variations? And are you trying to make the photo read as anything other than a technically good photo? Are you trying to convey or heighten – an emotion in the subject? Great post. Love the detail.

Tim,

Our studio is very collaborative, but at the same time the specialists are very hands on in their individual disciplines. In the case of this project, Chase and I had many discussions specific to the Seattle 100 aesthetic. This mostly happens early in the projects as the look is being developed. Once we have come to a place where we have a shared vision, the ball is squarely in my court to apply the vision to the entire collection.

Sick stuff! I love Black and white